Is It Afrobeats Though?

In 2024, South African pop phenom Tyla stood on the MTV Video Music Awards stage, ‘Best Afrobeats’ award in hand. She smiled, gave thanks, and marvelled at the doors her breakout hit Water had opened: both for herself, and for African music more broadly.

Then, in her distinct Jo’burg accent, she offered an elegant correction:

Amapiano isn’t Afrobeats, and African music is far more expansive than that label suggests.

South African Twitter was triumphant. Naija Twitter, still salty from her earlier Grammy win in a category widely read as Afrobeats-in-disguise, fumed. Ghanaian Twitter asked, yet again, why its artists were still locked out of these celebrations.

A decades-long tension revealed itself again: what do we call African music when it refuses to stay in the box the world puts it in?

We Are Polyrhythmic Peoples

To understand this tension, we need to understand the logics underneath our sound.

From as far back as our ancients and ancestors, polyrhythm has been central to African musical traditions. It allows multiple rhythms to exist at once, moving together without needing to align neatly. You can hear it in the drums that play during our traditional ceremonies. The result isn’t confusion or cacophony. It’s a richer, more layered form of coherence.

A language for those who are willing to learn it.

To be polyrhythmic is to be plural. To make room for contradiction, dissonance, and improvisation. It partly explains how artists from one country sometimes lay claim to genres from other countries. How Azonto and Amapiano can sit side-by-side in a DJ set. How someone like Amaarae can be pop, punk, experimental, and sensuous: all within a single track.

African music has always been made this way. It is layered, mobile, and hybrid. Like the African lives it reflects and celebrates, it doesn’t fit neatly into genre boxes.

And maybe that is why the Afrobeats label became a problem.

What’s in a Label?

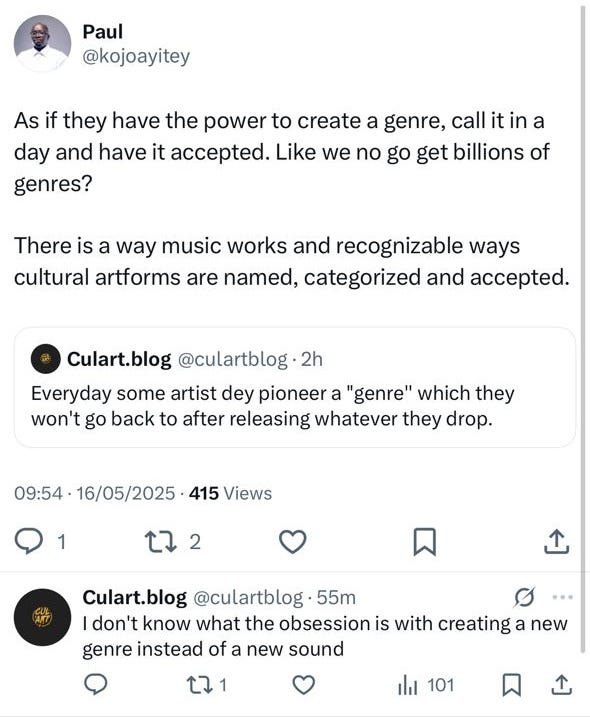

I left the cesspool of Twitter back in 2020, but I still get messages when arguments over the culture flare up. Most recently, a friend shared screenshots from when Ghanaian producer Nxrth of La Meme Gang announced a new hybrid genre he has decided to call, High-Pop: a blend of highlife and Western indie-pop.

Twitter wasn’t having it.

In fairness, even highlife didn’t name itself.

The term wasn’t coined by the people inside the ballrooms where it was being played by big bands like ET Mensah’s, but that’s a story for another day; one that a mentor of mine is preparing to tell, as he puts the finishing touches on a book on the matter.

Watch this space.

Being as old as I am, I remember back when artists like Erykah Badu, Common, The Roots and D’Angelo pushed back against the Neo Soul label that had been placed on them. I remember Erykah opening her classic, Mama’s Gun with a rock song, Common releasing his deliciously experimental (and, as a result, consistently underrated) album, Electric Circus. I remember how often Questlove spoke back then about the importance of creative freedom.

It’s easy to dismiss these kinds of things. At first glance, these moments might seem petty or parochial. But they raise important questions: Who gets to innovate? Who gets to define? And who gets written in… and written out?

Genre is never neutral. It’s about power. It shapes visibility; influencing who gets booked, who gets paid, who gets remembered. It decides whose history gets told and whose gets absorbed into someone else’s story.

When Yemi Alade tells CNN that highlife was birthed in both Ghana and Nigeria, and Ghanaians come for her, what’s at stake isn’t just national pride. It’s cultural memory, and whose version of the past gets to stand.

Afrobeats: A Blessing and a Trap

To be clear, the term Afrobeats did (and does) serve a purpose.

I once saw an interview in which Burna Boy said that the term had just “floated up from the streets of Lagos.”

Let’s immediately dispense with that myth.

Around 2011, UK clubs, blogs and radio shows were grasping for language to describe a new wave of West African music. It wasn’t “World Music” in the tired, problematic, Putumayo sense. It was different from the older sounds of the likes of legends like Youssou Ndour and Angelique Kidjo. And though it owed a debt to it, these sounds were different from the Afrobeat created by Fela Kuti and Tony Allen. The one without the letter ‘s’ at the end.

Enter Ghanaian-British DJ Abrantee.

When he was offered a slot on a major UK radio station to showcase the emerging sounds coming out of West Africa, he needed a name. He settled on The Afrobeats Show. And with that, a label was born: one that quickly became an umbrella for Ghanaian hiplife, Naija pop, azonto, and all their rhythmic cousins.

It was broad. It was catchy. It worked.

For a while.

But over time, the label began to collapse nuance. What started as a wide, open category began to solidify. It hardened into a genre: a kind of sonic shorthand in the eyes of DSPs (digital streaming platforms), award shows, and Western listeners.

Suddenly, Amapiano wins Afrobeats awards. Ghana disappears from “Afrobeats to the World” documentaries. Alté becomes a fashion trend.

Afrobeats came to stand for all contemporary African pop: even the kinds it was never meant to describe.

Afrofusion: Method Over Marketing

When Burna Boy says he doesn’t make Afrobeats but Afrofusion, he’s not just being contrarian. He’s trying to break free from a box (even if, by now, he’s a co-architect of that box). Afrofusion isn’t just something he pulled from thin air, though. It’s done been here, as our African American cousins might say. It’s a method that runs deep: older than Spotify categories and playlist marketing. Older than the genre tags that so often arrive after the fact.

Long before the platforms, African musicians were already making music that didn’t fit into fixed frames. Highlife was fusion. So was Fela’s Afrobeat. So was hiplife. So is asakaa. These weren’t pure forms. They were built from whatever was at hand: Ghanaian Osibisaba rhythms. Caribbean Calypso. American Jazz, Soul, Funk… and later Hip-Hop, and more.

They carried the marks of city life, migration, colonial residue, and diasporic dreaming.

To call them Afrofusion is to acknowledge that fusion isn’t the exception. It’s the method. It’s a way of admitting that African music has always been made in motion, and that its many musics have always been in ongoing conversation:

Not just across time.

But across space.

Africa’s Alté(rnative) Realities

Let me bring it home.

Over the past two decades, Accra has cultivated its own alternative scene: a sprawling constellation of artists, DJs, producers, and platforms pushing against the grain. It’s hard to define, partly because it doesn’t want to be.

Some lean into deep house and electronica. Others bend R&B. Some whisper queerness into lyrics. Others shout politics over 808s.

Much of this has been labelled alté, borrowing a term that did, in fact, emerge from Lagos (sharrouts to Boj of DRB LasGidi). But the spirit spills far beyond that. It moves through Nairobi, Kigali, Johannesburg, and beyond. And the truth is, artists across the continent were making alternative African music long before Lagos gave it a name.

That’s why I think of it all as alté(rnative): not just a single story of a scene, but a translocal ethic. It isn’t only about rejecting the mainstream. It’s about creative freedom.

It’s about expanding the map.

These scenes push past aesthetics. They carve out space for softness in cities with sharp edges. You can see it in small gigs with big feelings. In artists who choose collaboration over competition, lending equipment, sharing stems, and keeping each other afloat even when no algorithm is listening. In friends who show up for each other, even when they’re broke (or broken). There’s cultural care. Emotional care. Sonic care.

These are scenes not just of resistance, but of reimagining. And in many ways, they are Afrofusion at its most raw and experimental. More so than the chart-topping work of someone like Burna, these movements pull from a palette so diverse that it often bypasses what is popular entirely.

The point is freedom.

You know: that word etched onto Ghana’s coat of arms, right beside justice.

Yeah. That.

Genre: Gatekeeper in a Platform-Driven World

The more global African music becomes, the more vulnerable it is to mislabelling. Streaming platforms crave clarity. Award shows require categories.

And so, Amapiano gets filed under Afrobeats. Ghana gets edited out. Alté becomes a marketing moodboard.

Genre becomes a gatekeeper.

And yet, African music slips through the cracks. It doesn’t sit still. It moves, adapts, echoes, and mutates. It lives in contradiction as easily as in harmony. This is especially true of its alté(rnative) forms, but you’ll find it in the mainstream too, if you listen closely enough.

This is why it matters.

Because what we mislabel today is we misremember tomorrow.

Toward a New Vocabulary of Listening

So, where does this leave us?

Should we pay more attention to where sounds come from? To where they have been or where they are going? Maybe both

Maybe it starts with listening more carefully. Labelling more lightly. Finding ways to let artists define themselves in ways that honour the genres that shaped them without confining them… whether or not those labels will stick. We need room for musical traditions that might not always map neatly onto algorithms.

We can’t reduce everything African and rhythmic to a single catchphrase. That’s how genre turns into prison sentence instead of a guide.

Afrofusion, to me, is the umbrella under which all our modern music fits. But what I like about it is that it isn’t really a genre. It’s simply a description. A reflection of how we’ve been doing things for a very long time.

Some artists claim the name more explicity than others. Some apply it more deeply.

Either way, its ours:

A way of hearing how African music remembers, moves, and returns. Of hearing our history, and what our future may yet sound like.

Dr. D! Enough? NEVER. Didn't know the Kuti clan felt that way about Allen. Interesting! I'm a big big Adofo fan. Need to go back and refresh my knowledge. And yes to polyrhythms that transcend outsider understanding. It's really where it's at.

Well done, prof! Before the name Afrobeat was applied to Fela’s music, it was the name of his pet monkey. The Kuti family do not take kindly to Allen being mentioned as a co-architect in the same font size as Fela. What is debatable is if Fela wrote Allen’s percussion for him. Fela preferred African classical music later in life as he aimed toward the status of classical European genius, which was just another contradiction in his sense of standards, not quite divorced from the cancerous coloniality in the way he wished. Christian Adofo did a decent job in his book A Quick Ting about Afrobeats, tracing the name to an extent beyond Abrantee. He also claimed some legitimate territory for Ghana in Afrobeats lore. Reductive labels have their politics, gains and warts, but I love that our polyrhythms have always defied Eurocentric classifications; the genres of the African and black diaspora speak to each other in a language more fluent and comprehensible to our bodies in a way that our intellection must catch up with. And that is enough for now.